Work breakdown structure (WBS) is a key element for management planning, monitoring, and control of a project or a program scope. Regardless of the chosen life cycle (predictive, iterative, incremental, adaptive, or hybrid), WBS plays a role in almost every project. A WBS is important to further estimation—cost, duration, or resources, planning for resources, risk identification, schedule development, among others. It’s also used in earned value management (EVM).

In this article, I will cover the fundamentals of WBS with the definition, the key concepts which drive WBS development such as rolling wave planning and progressive elaboration, and best practices for using WBS in predictive (Waterfall) and adaptive (Agile) life cycles. I’ll also show how, with MS Project software, you can build a WBS in all possible project life cycles. We will conclude with the importance of a WBS in a project or program.

WBS Definition

The project management institute (PMI®) defines WBS as follows:

A WBS is a hierarchical decomposition of the total scope of work to be carried out by the project team to accomplish the project objectives and create the required deliverables.

The definition looks quite simple, but it’s a very significant statement for understanding the WBS. Let’s break it down.

- Hierarchical structure: The WBS is usually a hierarchical structure. It can present in a graphical format, tree form, or a tabular structure, but it will always be hierarchical in nature. The highest level of the WBS is known as Level-1 and followed with Level-2. It can continue to Level-N.

- Decomposition: The total scope of project work is considered and the team breaks down the work into manageable chunks. That’s why in the name WBS, we have a term breakdown. The decomposition or breakdown of the WBS creates the various levels, deliverables, and work packages. As you follow the breakdown, each descending level of WBS represents a further detailed definition of the work to be done.

- Deliverable: The deliverable is the unique, verifiable product, service, or result produced. The WBS is usually deliverable oriented when you do the decomposition. Based on the WBS, deliverables are created by the project team.

The previous statement of deliverable-oriented breakdown will enable us to understand how to actually break the project or program scope down to create the WBS.

WBS Examples

Let’s take, for example, the writing of a book. Say you are writing a book on risk management. You want to have deliverables in terms of “Manuscript,” “Write Book,” “Edit Book,” and finally, “Publish Book.” Under “Write Book,” you have the individual chapters to be written (Chapter 1, Chapter 2, and so on). Similarly, under “Edit Book,” you’ll want to edit the individual chapters. In such a case, the WBS would be represented as shown.

At the highest level, i.e., Level-1 (L1), we have the name of the book. In the next level, i.e., Level-2 (L2), we have the phases of writing, such as “Write Book,” “Edit Book,” and “Publish Book.” Next, “Write Book” is broken down into “Chapter 1,” “Chapter 2,” “Chapter 3,” and so also with the other WBS elements in levels. At the lowest level (L3), we have more details on each chapter (“Project Risk,” “Project Risk Management,” and “Agile Risk Management” and so on).

You may have noticed that I’ve assigned a numbering system to each element of the WBS, i.e., “1.2.2.2 Enterprise Risk Management.” The number used is the WBS identifier (ID), and is called the WBS code. This code or identifier uniquely identifies each element of the WBS. The WBS code is part of the WBS dictionary, which has detailed information about each element of the WBS.

But, let’s say you want to have a delivery in terms of your book’s chapters, i.e., Chapter 1 followed by Chapter 2, which in turn is followed by Chapter 3, and so on. In this case, the WBS would be shown as below.

Can you see the differences between the previous WBS and the current one?

In the first WBS, the breakdown is in terms of writing the complete book, followed with editing the book, and finally, its publication. However, in the second WBS, the breakdown is in terms of writing, editing, and publishing individual chapters.

Depending on how you want to deliver, the WBS is built accordingly.

The lowest level of the WBS is known as the work package, where you can estimate for cost and duration. A work package is further broken down into activities, but these are not shown in the WBS, because activities are used in schedule management. The WBS can also have planning packages, which unlike work packages, are without the activities. Planning packages are put in the WBS for known, but unplanned work, whereas the work packages will have both known and planned work.

Above the work package level, there is a control account, where management control is exerted. The approved version of the total scope of work or scope statement, WBS, and WBS dictionary constitute the scope baseline.

At this stage, some questions may be coming to your mind:

- What should be done when one can’t decompose to the level of the work package?

- How can we implement further schedule or cost planning as they are based on the WBS?

This leads us to the concepts of progressive elaboration and rolling wave planning.

Progressive Elaboration and Rolling Wave Planning

Many management practitioners mistakenly think the concepts of progressive elaboration and rolling wave planning are only applicable in Agile environments. It need not be the case. In fact, these concepts apply both to traditional/Waterfall and adaptive/Agile projects.

Let’s first consider the definition of progressive elaboration. As per PMI:

Progressive elaboration is the iterative process of increasing the level of detail in a project management plan as greater amounts of information and more accurate estimates become available.

It’s highly possible that in a traditional project, there will be elements in the WBS which can’t be broken down further. As and when more clarity comes to those WBS elements, this can be done iteratively. This is progressive elaboration.

One key aspect of Agile development is its iterative nature. The concept of progressive elaboration fits with iterative development—more of which we will see shortly. Decomposition in an Agile project can happen with progressive elaboration, i.e., while building the product backlog, the backlog items are detailed progressively according to their priorities.

Rolling wave planning is a form of progressive elaboration. PMI defines rolling as planning as:

An iterative planning technique in which the work to be accomplished in the near term is planned in detail, while the work in the future is planned at a higher level.

In Agile, rolling wave planning happens with project planning, release planning, and iteration planning. For example, while at the release level, the plan is at a higher level, and for the immediate next iteration, the plan is more detailed and granular.

Agile – Iterative and Incremental

The Agile life cycle is both iterative and incremental, i.e., the product, result, or service is delivered in a series of iterations in an incremental way. To understand all possible life cycles in a project, refer to this article, Why and When to Go for Agile Life Cycle.

Let’s reuse our book example from earlier to understand how we can apply WBS in Agile mode. We want to write a book in an iterative and incremental way.

Iterative development is based on this premise:

We rarely get anything right for the first time, and it takes time to get anything right! Hence, iterate.

This is especially true in an environment when change is high, requirements are highly uncertain, and scope has differing perceptions among stakeholders. In such a case, we iterate. The focus in iterative development is learning optimization, rather than speed of delivery.

When writing a book, I wouldn’t complete ONE chapter in just one go. I would write, edit, delete, and rewrite the content of a chapter many times. The first version is usually a poorly written one, which gets better with feedback and iterations. In fact, while writing this article, I’ve followed the iterative mode of development, where I iterated the sections of this article multiple times.

Incremental development, on the other hand, is based on this premise:

It is better to build some of it (the product, service, or result) than to build all of it! Hence, deliver incrementally.

Again, taking the example of the book, I wouldn’t complete ALL the chapters in one go. Rather, I’ll write one chapter at a time and deliver it to an initial audience who wants to have a look. While editing the first chapter and writing the second, I’ll incorporate their feedback. The next chapter is built on top of the first chapter, and the subsequent chapters will be built on top of the previous ones – hence, the book develops in an incremental way. The focus in incremental development is speed of delivery.

While writing this article, I’ve also used incremental mode, i.e., I completed the first incremental cut and shared it with Jana Phillips, my editor. Jana has checked, added, and edited the article, providing me with her feedback. There may have been a new section added for the next incremental stage. In the final build, I’ll review it again and advise if anything more is needed. Finally, we go live with publication by the MPUG team (republished here).

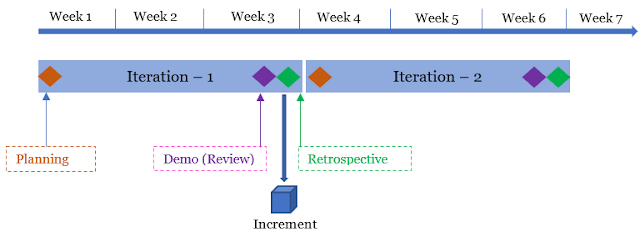

Agile development combines and leverages both iterative development with improved or optimized learning and incremental development with speed of delivery. This is depicted below.

WBS in Predictive Life Cycle

In a predictive life cycle model, requirements are fully known, change is low, and risk is also low. Hence, the phases in a project can be sequentially executed, though the final product (or service or result) is delivered at the end of the final phase.

Taking our book example, one can say the following phases of the project create the book. (I’ve made the phases a bit more formal compared to the previous example.)

- Research

- Design

- Development

- Delivery

With the adoption of these phases, the WBS will become as is shown below.

At L1, you have the project name, i.e., “Book – Risk Management.” At L2, you have the various phases. The level-2 elements of the WBS are further decomposed to finally give us the work packages:

- “1.2 Design” is broken down to “1.2.1 Front Cover” and “1.2.2 Back Cover.”

- “1.3 Development” is broken down to “1.3.1 Write Book” and “1.3.2 Edit Book,” which are further broken down to the individual chapter level.

With Microsoft Project as your tool, you create and plot the WBS quickly as I’ve shown in the next figure.

The default WBS code for the WBS elements (i.e., 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 …) can be shown by enabling the “Outline Number” under the Format tab. You can also create custom WBS codes with the help of this tool. The graphical side has various timescales, and, in our case, it has three tiers—the top tier in quarters, middle tier in months, and the bottom tier in weeks.

WBS in Agile Life Cycle

In Agile approaches, the scope of a project is not clearly known from the beginning. It evolves throughout the lifecycle. All the requirements, features, epics, and stories for the project are part of the (Product) Backlog, as this article explains.

Though WBS is often associated with predictive lifecycles, in Agile approaches, WBS can be used. The scope of an Agile project is supported by the backlog. In Agile development, epics are decomposed into user stories, just like high level elements in a traditional WBS are finally decomposed into work packages. Also, as the work package represents the lowest level in a WBS, (user) stories will represent the lowest level of a WBS in an Agile project. In other words, you could say work packages in an Agile WBS will be equal to the (user) stories.

You may be wondering how to decompose from the project level to the user story level. There are many approaches, but for this piece we will explore a Project to Release to Iteration to (User) Stories scenario. The project is divided into multiple releases. Each release will have many iterations, and, in every iteration, we will deliver a set of features (an entire chapter, part of a chapter, or design of the book). The features can be estimated in story points. I’ve selected this decomposition approach to be consistent with my previous article on Agile Release Planning.

As we already know, Agile is both iterative and incremental. Hence, we have to deliver incremental value in every iteration.

As shown above, at L1, you have the project name, i.e., “Book – Risk Management.” However, at L2, you have the various releases shown. The level-2 elements of the WBS are the further decomposed iterations (L3), and in every iteration, we will deliver the chapters (L4) estimated in story points. This level could be considered the work package level for this Agile WBS.

Like with the traditional WBS, with MS Project, this WBS can be as easily created. The software tool supports a Scrum framework, where iterations are known as Sprints. The created WBS is shown below.

As shown in the above WBS, we have releases broken down into Sprints, and in each Sprint, we will be delivering a chapter or part of a chapter. This is a tabular view of the WBS and can be seen in Sprint Planning Sheet view.

You can switch to the Gantt Chart view to see the graphical depiction of the chart, which is shown below.

Conclusion

While the scope defines the why of the project, the WBS tells the what of the project. It doesn’t inform how or when the deliverables will be produced or who will produce the deliverables.

The how part of the project comes later and is informed by the activities or tasks of the project. The how much part of the project also comes later and is typically addressed under the umbrella of cost management. The when part is best described by the project schedule. The who part of the project is addressed by resource management, i.e., the team members who will be executing the projects to give the required deliverables.

Nevertheless, it’s the what part of the project, the Work Breakdown Structure, which drives these other aspects—the how to do, when to do, how much money will it take, and who will do it. The WBS provides a clear vision of the total scope of work involved in a project and is the beginning stage of defining the deliverables—both intermediate and final deliverables—to be created. Due to its visual nature, the WBS is an effective communication tool used by managers in a project or a program.

--

This article was first published by MPUG.com on 18th August, 2020. This is a refined version.

References

[1] PMP Live Lessons – Guaranteed Pass or Your Money Back, by Satya Narayan Dash

[2] MS Project Live Lessons with Money Back Guarantee, by Satya Narayan Dash

[3] Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) Guide, 6th Edition, by Project Management Institute (PMI)

[4] Book: I Want To Be A PMI-ACP: The Plain and Simple Way, 2nd Edition, by Satya Narayan Dash

Videos Courses on MS Project Agile and Hybrid-Agile:

[1] Mastering MS Project Agile (Scrum and Kanban)

[2] Certified Hybrid-Agile Master Professional