“I keep six honest serving-men,

They taught me all I knew,

Their names are What and Why and When,

And How and Where and Who.

I send them over land and sea,

I send them east and west,

But after they have worked for me,

I give them all a rest.”

– From the poem, “The Elephant’s Child,” by Rudyard Kipling

Long ago, in my childhood days, I was introduced to the fascinating world of poetry by my father, who brought a variety of poems and stories from writers and authors around the world to me. “The Elephant’s Child” was one of them.

This poem in particular has been used as a method. That is, the Kipling method. One of communication management, risk identification, charter preparation, and also, product development. With this method, one gets various ideas considering multiple aspects: What, Why, When, Where, Who, and How. It’s also known as the 5W1H method. In this article, we will learn about a technique called Story Mapping, where this method can be employed as an initiation point.

With the 5W1H method, when starting product development or creating a service or solution, one asks questions such as the following:

- What needs to be built?

- Why are we building it?

- For whom are we building?

- When will it be needed?

- Where does this fit in?

- How are the customers going to use it?

Jeff Patton, the creator of the User Story Mapping technique, explains the building of the map in six simple steps. They are:

- Frame the idea or problem

- Map the big picture

- Explore

- Slice out a release strategy

- Slice out a learning strategy

- Slice out a development strategy

The above 5W1H questions address the initial steps. It is important to remember that these questions get the conversations rolling. Shared conversations and shared understanding can then occur, as those aspects are what stories are mainly about.

Story Map Definition

As you may have noticed, this article is about Story Mapping, not User Story Mapping. There can be varieties of stories: spike stories, analysis stories, risk stories, and architectural stories, among others. I’ve seen all such stories being part of the map, and hence, will be using the term, Story Map.

Let’s begin with the definition of a story map.

Story map is a grid-like graphical representation of epics and stories in a sequenced order based on their business value and the order in which the stakeholders will execute them. When read from left-to-right of the map, it tells a big story in a sequence of steps, whereas when read from top-to-bottom, it gives more details about each step.

After you have framed the idea or problem with the 5W1H questions, you can begin to build a story map at a very high level with the help of above definition.

The customer, user, or subject matter expert may tell the story of the product being built in a sequence of steps. Each step is written on a sticky note, index card, or electronic card horizontally (from left to right). Then, under each step, the details are written on another set of cards, and this time, placed vertically from top to bottom. This forms a grid-like structure as shown below. This is a story map.

In his book, Jeff Patton calls the steps from left to right, “Activities”. Under each activity, you have a set of “tasks”, which you get when you break-down or decompose the activities.

As shown, the story is told by a user from left-to-right in a sequence of steps—each step being an activity. This sets the narrative flow. Under each activity, we have a set of tasks decomposed from the respective activity, and they are placed vertically from top-to-bottom.

With this basic understanding, let’s go a bit deeper and understand the various components of a Story Map.

Going forward, I’ll be using terms such as Epics (in place of Activities) and Stories (in place of Tasks), to maintain consistency with an earlier article on Agile development. In the real world, it doesn’t matter which terminologies you use, if you understand the concept and can apply it while building your product or solution.

Building Blocks in a Story Map

Personas

The story telling for a story map starts with the persona. Persona is usually taken for a user, but in this case, I’ve extended it to stakeholders. The persona is an imaginary representation of the stakeholder role used while describing a story. You may express this element as the needs of an imaginary stakeholder. The persona can have likes, dislikes, a job, and goals, among other aspects. A persona plays a role in the organization—the role is real, but the persona is not.

The epics are considered from the persona’s perspective. For example, the story explains how the stakeholder is going to use the product or solution. Comparing a story map to a human being, you can say the persona will act as the head of the story map. The first thinking part starts here.

For story mapping, there can be many personas – not just one. This is similar to a human being who grows with input from many. When working with personas, a variety of stakeholders in various roles should be considered, who will interact with the product being built.

Backbone

Without a spine, a human can’t function, and similarly, without a backbone, a story map can’t function. The backbone provides the minimum set of capabilities needed to deliver the product or solution or service. This can also be called the minimum viable product (MVP). The backbone usually consists of features and epics.

Walking Skeleton

Just below the backbone, we have the map’s body part. The body consists of the walking skeleton. Again, making a comparison to the human body, you can say the walking skeleton is the story map’s skeleton, too. Just like the human body’s skeleton, without the walking skeleton, the product would be non-functional.

The walking skeleton is the complete set of end-to-end functionalities that make the product or solution acceptable. This part of the story map’s body usually consists of stories, including the user stories. This set of stories make the product minimally functional, and hence, can be called the minimum marketable features (MMF).

Under each story of the walking skeleton, you can have more stories arranged vertically. Higher priority stories will be at the top, whereas lower priority ones will be at the bottom.

When you combine the personas, the backbone, the walking skeleton, and the additional stories below the walking skeleton, you get the Story Map, as represented in the below figure.

The stakeholder starts telling the big story in a sequence of steps, which are represented as epics. This constitutes the backbone. While building the backbone, the principle of “mile wide, inch deep” or “kilometer wide, centimeter deep”, as Jeff beautifully puts it, is followed. It means we get to the end of the big story, before diving deep into the details.

The walking skeleton is below the backbone. When you decompose the epics in the backbone, you get the stories in the skeleton—ones that make the product minimally functional. Below the walking skeleton you have more stories, which are ordered.

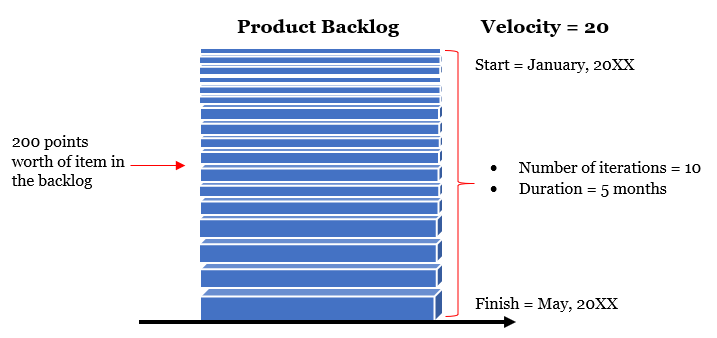

Release Planning with a Story Map

After you have placed the epics, stories, and features in the story map based on the team’s capacity to deliver, releases can be determined. This is where the release strategy is sliced out from the story map.

As we already know, the backbone includes all the absolute essential parts of the product. These are items that you just can’t prioritize because they have to be in the product. Next to the backbone, we have the walking skeleton, which has the minimum marketable set of features. Hence, our first slice for the release consists of these two, and possibly some more stories, below. In the next slice (for another release), we can take more stories and create another release, and so on. This is shown in the figure.

As you can see, in the first release we have the backbone and stories from the walking skeleton, along with one story below the backbone. In our second release, we have more stories taken, which are from below the backbone. Remember that these stories are ordered based on their business value.

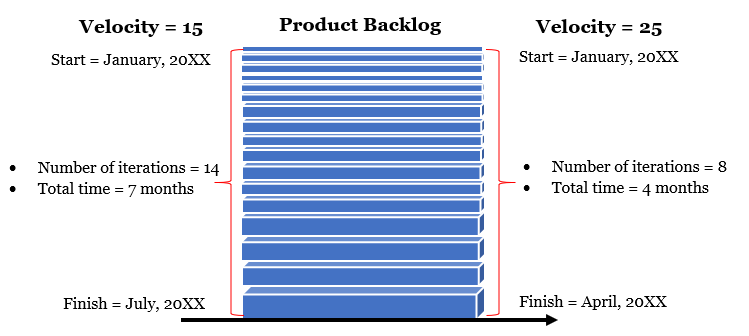

Story Map vs Product Backlog

At this stage, you may be wondering why one should go for a Story Map rather than a Product Backlog?

After all, the product backlog also has all the epics, features, and stories in a single file. It can also have release slices. There are quite a few differences between the two, but I’ll note the most significant ones:

- While working with the product backlog, it’s easy to get lost in the details. Team members will be working on tasks, but they don’t see the big picture. You can literally miss the forest for the trees! With a story map, all members of the team see the big picture. This, in my view, is the most significant benefit of a story map over a product backlog.

- The story map is a two-dimensional visual structure, whereas the product backlog is a one-dimensional flat structure. Story mapping, on its own is also a prioritization technique—it’s just that it is done in a visual way.

- Dependencies can’t be easily shown in a product backlog as long as it’s a flat one, whereas dependencies can be represented visually and more clearly with a story map.

So, which should one use?

Note: You can learn the various differences between Story Map and Product Backlog in the below detailed post.

Agile Asanas: Story Map Vs. Product Backlog - The Differences

The primary idea behind telling stories is communication. As noted earlier, it’s about shared conversations and shared understanding. You may think of using both the story map and product backlog in a single map, which is shown in the below figure.

The product backlog is just below the story map with a set of index cards or sticky notes, which are the backlog items. When needed, you can pull the prioritized ones into the story map. Don’t just go by the lumped-up cards in the backlog. Remember, you can order them as well.

It’s up to you as the Product Manager or Product Owner in consultation with your Project Manager and team members to decide which one best works for the team.

At this stage, it’s pertinent to note that like a Product Backlog which is never complete, a Story Map is also never complete. When new feature requests come up or enhancement requests are made, you can add, arrange, and order them within the story map.

A Practical Story Map

Let’s look at a real-world example to understand story mapping further. I’ll use my previous example of a flight ticket reservation portal, where I had explained various types of stories.

We will first start with the possible stakeholders (personas) who will be using this portal:

- Normal Traveler

- Business traveler

- Frequent Flier

- Booking Agent

- Vacation Traveler

- … you can add more.

You need not work on all of them, but can take just one to build the MVP consisting of the backbone and walking skeleton. For our example, let’s take the “Business Traveler.”

Considering the business traveler, we need to determine the big story in a sequence of steps. These steps will form the backbone or set of epics. These epics, when broken down, will provide the stories, which are listed next to them.

The epics are noted in the below table. Can you think of the associated possible stories?

Go ahead and try it.

The associated stories for the epics are noted in the below table. Your answer may vary, but you’re right if you tried to break-down and get to the related stories.

The above stories can be put in the usual story format. For example, you can say: “As a business traveler, I want to register via e-mail, so that I can sign-up for the portal.”

I’ve also noted the epics in the above table in single words. Search for a flight is simplified to “SEARCH,” select a flight becomes “SELECT,” and so on. This is for simplicity and to keep our high-level goals focused. When we take these epics and put them as a sequence of steps for the business traveler, we will get the following figure.

As shown, the story of a business traveler using the portal listed horizontally in a sequence of steps. The traveler will first sign-up, then search for a flight, and then select the flight. The traveler will pay for the tickets, and finally, close-out his/her interaction with the portal. These steps form our backbone.

Next, we will take the first big activity or epic, “SIGN-UP,” and arrange the stories associated with it vertically, as shown below. If you created your own stories, go ahead and put them below the respective epics within the structure of the backbone. This results in the walking skeleton and more stories below it.

Next, we slice out the releases from the map.- For the backbone, we will have SIGN-UP, SEARCH, SELECT, PAY, and CLOSE.

- For the walking skeleton, we will have “new user registration” and “log-in” from “Sign-up,” “search by journey start/end dates” from “Search,” “Choose by shortest flight duration” from “Select,” “pay via credit card” from “Pay,” and “logout” from “Close.”

Your first release slice may look differently depending on the epics and stories you have chosen to start with. If your team has the capacity, take more. If this is the case, when you slice out the first release, it will result as shown below.

For subsequent releases, you and your team can decide which other stories are to be taken up.

That’s it! If you have understood so far and are able to slice out your first few releases in the map, you have understood the concept of story mapping well. It’s a long-read. But, I believe, if you have read it, worked on it, and gone through it honestly, it’s time to take a rest, as the poem I opened with says.

If you have comments, new views, or suggestions, do share them below.

This article is dedicated to the memory of my father, the late Harendra Nath Dash, who passed away last year on June 11. I miss him every day and feel his absence. He first introduced me to the world of poetry, stories, and books, so this is a tribute to him and his teachings.

--

References:

[1] User Story Mapping – Discover the Whole Story, Build the Right Product, by Jeff Patton with Peter Economy

[2] I Want To Be An ACP: The Plain and Simple Way To Be A PMI-ACP, 2nd Edition, by Satya Narayan Dash

[3] The PMI Guide to Business Analysis, by Project Management Institute (PMI)